Pan's Labyrinth (and Tom's Palette)

Don't say I ne'er try hor. But boring lei.

The week started with tickets in hand for Guillermo del Toro's El laberinto del fauno (Pan's Labyrinth. "Faun" = "Pan" 'cos it just sounds better.).

The week started with tickets in hand for Guillermo del Toro's El laberinto del fauno (Pan's Labyrinth. "Faun" = "Pan" 'cos it just sounds better.).

*Spoilers abound gloriously*

Pale men with eyes embedded their palms like stigmata (the horrific biological inefficiency of it all!) aren't quite our cup of tea. Narrative-flow sagging like folds of loose skin aren't quite our thing either.

But after Tom's Palette (thanks to Spots and ieat), and after the Baghdad Street sarabat hole-in-the-wall, 3 things still niggled:

El laberinto del fauno presents 2 worlds:

Additionally, parallels abound between the 2 worlds, perhaps suggesting that Ofelia is merely incorporating her "real life" experiences in her "fantasy": the layout of the Captain's dining room seems to be the same as that of the Pale Man, there is the key to the storeroom and the golden key from the second task, and there is the knife Mercedes uses to cut vegetables and stab the Captain and the knife Ofelia gives to the Faun, with which the Faun threatens to shed the blood of Ofelia's baby halfbrother.

But yet there are hints that the Underworld is real after all: the chalk door actually gets Ofelia from her attic bedroom to the Captain's office and at a dead end, the labyrinth walls open for Ofelia but not for the Captain.

DarknessGreyness of the Fairy Tale

Happily, the labyrinth of the Faun is nothing like the all-singing all-dancing glam muppet Labyrinth of memory with David Bowie and Jim Henson's cuddly creatures. And thankfully, there was no sanitising Disneyfication either. Just (almost) the good old original grimness of the Brothers Grimm.

Loved the shadows, the palette (especially, the greybluegreen of the Underworld, all ancientness and organicness and ambiguity), the texture and the sound design (the creaking and wind-through-tree-branches of the Faun's limbs and the perfectionistic squeaking of the Captain's shiny black leather boots).

Loved the shadows, the palette (especially, the greybluegreen of the Underworld, all ancientness and organicness and ambiguity), the texture and the sound design (the creaking and wind-through-tree-branches of the Faun's limbs and the perfectionistic squeaking of the Captain's shiny black leather boots).

In their own fashion, fairy tales are not ways to escape reality but ways to articulate it. Fairy tales (unemasculated, unsweetened) help children learn not about the black and whites, but about the greyness of the world.

In the 1944 world as in the real world, people and the relationships between people are grey. Captain Vidal is smart in his uniform. He shaves carefully in the morning, his hair is black and shiny like his boots, he is well-groomed, well-spoken, and gentlemanly enough to get up from his chair when his wife enters and leaves the room. He is courageous in armed combat. He is a Mel-Gibson Die-Hard hero in a fascist uniform who fixes his own watch and sews up his own Chelsea grin. His men respect him. Yet he is no hero in the show: he tortures with pleasure and kills without good reason and without mercy.

In the 1944 world as in the real world, people and the relationships between people are grey. Captain Vidal is smart in his uniform. He shaves carefully in the morning, his hair is black and shiny like his boots, he is well-groomed, well-spoken, and gentlemanly enough to get up from his chair when his wife enters and leaves the room. He is courageous in armed combat. He is a Mel-Gibson Die-Hard hero in a fascist uniform who fixes his own watch and sews up his own Chelsea grin. His men respect him. Yet he is no hero in the show: he tortures with pleasure and kills without good reason and without mercy.

The Faun too is an ambiguous creature. "My mother told me never to trust fauns," Mercedes advises Ofelia and we are unsure if the Faun can be trusted. At the second task, his fairies appear to give Ofelia the wrong instructions. And if the Faun was really one of Ofelia's subjects, he wasn't too keen on having her complete the last task after she'd got 2 of his fairies eaten.

The Faun too is an ambiguous creature. "My mother told me never to trust fauns," Mercedes advises Ofelia and we are unsure if the Faun can be trusted. At the second task, his fairies appear to give Ofelia the wrong instructions. And if the Faun was really one of Ofelia's subjects, he wasn't too keen on having her complete the last task after she'd got 2 of his fairies eaten.

Motif of Obedience

Motif of Obedience

The Faun tells Ofelia that she will have to pass 3 tests before the full moon. The point is to ensure that her spirit is intact and that she hadn't become mortal.

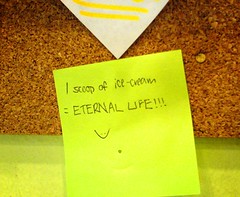

What does it mean to be mortal? The film suggests that mortality is blind obedience. Presented with a choice, Mercedes and the doctor choose to disobey the Captain and help the rebels. Says the doctor to the Captain just before he is killed,"To obey without questions is something only people like you can do." Ofelia chooses to disobey the Faun (who'd earlier demanded strict unquestioning obedience after the fiasco with the Pale Man) and in so doing gains eternal life (at some point, the film conflates passing the tests and so returning to the Underworld as gaining eternal life. There are images of the Rose of Eternal Life, featured earlier in the film, on Ofelia's yellow enthronement dress).

A quick read up on Del Toro shows him reiterating on several occasions that he is proud to be a lapsed Catholic. But it is interesting that having rejected Catholicism (which he equates with Christianity), he offers a tale of redemption and a yearning for something more. If disobedience on a pedestal was his aim, why the gold on gold throne scene and reunion with family in the end?

A quick read up on Del Toro shows him reiterating on several occasions that he is proud to be a lapsed Catholic. But it is interesting that having rejected Catholicism (which he equates with Christianity), he offers a tale of redemption and a yearning for something more. If disobedience on a pedestal was his aim, why the gold on gold throne scene and reunion with family in the end?

Yet, understandably, this tale is not the same as the gospel, because while it reminds us of the need to be discerning, to tell between truth and untruth, it lacks one major ingredient of the gospel, the ingredient for which we give God glory and praise and the reason why the gospel is the "good news": it lacks grace - the admittance to The Better World of one not worthy of admission, the entry into heaven of one who does not deserve to enter.

*all Pan's Labyrinth images from Dark Horizons

The week started with tickets in hand for Guillermo del Toro's El laberinto del fauno (Pan's Labyrinth. "Faun" = "Pan" 'cos it just sounds better.).

The week started with tickets in hand for Guillermo del Toro's El laberinto del fauno (Pan's Labyrinth. "Faun" = "Pan" 'cos it just sounds better.).*Spoilers abound gloriously*

Pale men with eyes embedded their palms like stigmata (the horrific biological inefficiency of it all!) aren't quite our cup of tea. Narrative-flow sagging like folds of loose skin aren't quite our thing either.

But after Tom's Palette (thanks to Spots and ieat), and after the Baghdad Street sarabat hole-in-the-wall, 3 things still niggled:

- the reality of the worlds;

- the darkness of the fairy tale; and

- the motif of obedience.

El laberinto del fauno presents 2 worlds:

- the world of 1944 post-Civil War Spain where Ofelia's fascist stepfather, Captain Vidal, is bent on cleansing a small village of a motley crew of Republican militia; and

- the world of a faun, of fairies, of curious monsters, where Ofelia (tragic lass in Shakespeare's Hamlet?) is actually a princess, the long-lost daughter of the king of Hades, where she must perform 3 tasks before she will be able to return to her rightful home.

- Captain's White-Rabbit (the OCD in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, not the local sweet) watch-checking fetish;

- Ofelia's Alice-in-Wonderland party dress (except that, down down down the tunnel, is a slimy giant frog);

- Ofelia's succumbing to the temptation of the food on the banquet table despite being rather well-fed, echoing the greed of Edmund for the Turkish Delight of the White Queen;

- the Pale Man tearing off the heads of the fairies in a delightful way reminiscent of Polyphemos and also Francisco de Goya's Saturn Devouring His Son (which hints that the fairies in question weren't really getting their heads bitten off. Sure enough, they appear again in the enthronement scene).

Additionally, parallels abound between the 2 worlds, perhaps suggesting that Ofelia is merely incorporating her "real life" experiences in her "fantasy": the layout of the Captain's dining room seems to be the same as that of the Pale Man, there is the key to the storeroom and the golden key from the second task, and there is the knife Mercedes uses to cut vegetables and stab the Captain and the knife Ofelia gives to the Faun, with which the Faun threatens to shed the blood of Ofelia's baby halfbrother.

But yet there are hints that the Underworld is real after all: the chalk door actually gets Ofelia from her attic bedroom to the Captain's office and at a dead end, the labyrinth walls open for Ofelia but not for the Captain.

Happily, the labyrinth of the Faun is nothing like the all-singing all-dancing glam muppet Labyrinth of memory with David Bowie and Jim Henson's cuddly creatures. And thankfully, there was no sanitising Disneyfication either. Just (almost) the good old original grimness of the Brothers Grimm.

Loved the shadows, the palette (especially, the greybluegreen of the Underworld, all ancientness and organicness and ambiguity), the texture and the sound design (the creaking and wind-through-tree-branches of the Faun's limbs and the perfectionistic squeaking of the Captain's shiny black leather boots).

Loved the shadows, the palette (especially, the greybluegreen of the Underworld, all ancientness and organicness and ambiguity), the texture and the sound design (the creaking and wind-through-tree-branches of the Faun's limbs and the perfectionistic squeaking of the Captain's shiny black leather boots).In their own fashion, fairy tales are not ways to escape reality but ways to articulate it. Fairy tales (unemasculated, unsweetened) help children learn not about the black and whites, but about the greyness of the world.

In the 1944 world as in the real world, people and the relationships between people are grey. Captain Vidal is smart in his uniform. He shaves carefully in the morning, his hair is black and shiny like his boots, he is well-groomed, well-spoken, and gentlemanly enough to get up from his chair when his wife enters and leaves the room. He is courageous in armed combat. He is a Mel-Gibson Die-Hard hero in a fascist uniform who fixes his own watch and sews up his own Chelsea grin. His men respect him. Yet he is no hero in the show: he tortures with pleasure and kills without good reason and without mercy.

In the 1944 world as in the real world, people and the relationships between people are grey. Captain Vidal is smart in his uniform. He shaves carefully in the morning, his hair is black and shiny like his boots, he is well-groomed, well-spoken, and gentlemanly enough to get up from his chair when his wife enters and leaves the room. He is courageous in armed combat. He is a Mel-Gibson Die-Hard hero in a fascist uniform who fixes his own watch and sews up his own Chelsea grin. His men respect him. Yet he is no hero in the show: he tortures with pleasure and kills without good reason and without mercy. The Faun too is an ambiguous creature. "My mother told me never to trust fauns," Mercedes advises Ofelia and we are unsure if the Faun can be trusted. At the second task, his fairies appear to give Ofelia the wrong instructions. And if the Faun was really one of Ofelia's subjects, he wasn't too keen on having her complete the last task after she'd got 2 of his fairies eaten.

The Faun too is an ambiguous creature. "My mother told me never to trust fauns," Mercedes advises Ofelia and we are unsure if the Faun can be trusted. At the second task, his fairies appear to give Ofelia the wrong instructions. And if the Faun was really one of Ofelia's subjects, he wasn't too keen on having her complete the last task after she'd got 2 of his fairies eaten. Motif of Obedience

Motif of ObedienceThe Faun tells Ofelia that she will have to pass 3 tests before the full moon. The point is to ensure that her spirit is intact and that she hadn't become mortal.

What does it mean to be mortal? The film suggests that mortality is blind obedience. Presented with a choice, Mercedes and the doctor choose to disobey the Captain and help the rebels. Says the doctor to the Captain just before he is killed,"To obey without questions is something only people like you can do." Ofelia chooses to disobey the Faun (who'd earlier demanded strict unquestioning obedience after the fiasco with the Pale Man) and in so doing gains eternal life (at some point, the film conflates passing the tests and so returning to the Underworld as gaining eternal life. There are images of the Rose of Eternal Life, featured earlier in the film, on Ofelia's yellow enthronement dress).

A quick read up on Del Toro shows him reiterating on several occasions that he is proud to be a lapsed Catholic. But it is interesting that having rejected Catholicism (which he equates with Christianity), he offers a tale of redemption and a yearning for something more. If disobedience on a pedestal was his aim, why the gold on gold throne scene and reunion with family in the end?

A quick read up on Del Toro shows him reiterating on several occasions that he is proud to be a lapsed Catholic. But it is interesting that having rejected Catholicism (which he equates with Christianity), he offers a tale of redemption and a yearning for something more. If disobedience on a pedestal was his aim, why the gold on gold throne scene and reunion with family in the end?Yet, understandably, this tale is not the same as the gospel, because while it reminds us of the need to be discerning, to tell between truth and untruth, it lacks one major ingredient of the gospel, the ingredient for which we give God glory and praise and the reason why the gospel is the "good news": it lacks grace - the admittance to The Better World of one not worthy of admission, the entry into heaven of one who does not deserve to enter.

*all Pan's Labyrinth images from Dark Horizons

3 Comments:

I actually thought this movie can be use as a diagnostic tool in the assessment of personality.

I'm thinking of making a standardized personality test using the movie.

Question 1. Do you think the movie had a happy ending or sad ending?

p.s. I was so hoping something magical would happen everytime there was a sad scene.

Have you watched Babel?

Del Toro is not a Christian, so I'm not surprised that we can't draw a clear, perfect allegory to the gospel. But because the gospel is true, and Del Toro wants to strike something true, he ends up catching echoes of the truth. And I disagree with the claim that grace is absent from the film. Ofelia disobeys. She fails. The faun condemns her. But then, inexplicably, he comes back and says, "I will give you another chance." Sure, this still means Ofelia must succeed in order to be saved, but that second chance is a trace of grace, an echo of the truth, that even though we have fallen short in our calling to serve God, we are granted something we do not deserve. And in view of that "second chance," we must "work out our salvation with fear and trembling."

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home