Three Days Of Reading Haruki Murakami

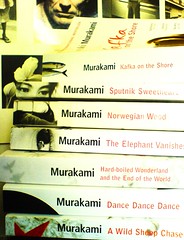

Not having the benefit of frequent London transportation strikes unlike some, we made do with the National Day holiday and the recent weekend to get stuck into a certain much-feted author. Besides, Borders was selling 3 Haruki Murakamis for the price of 2. Would have preferred the ones with John Gall's cover art. But a discounted book is a discounted book.

[Sidenote 1: Yes, I'm very left in the dust behind the Murakami fan-wagon. ;-). Aiyah. Haven't read much fiction since secondary school.]

[Sidenote 2: The Red Dot Traffic Building houses a nice quiet Pacific Coffee Company outlet with cushy red plush armchairs, leather sofas and Vietnamese paper lamps that is highly conducive for long-term Murakami reading.]

On a blasphemously quick read of many of his books within 3 days, the catchy universality of Murakami, it seems, stems less from his Western cultural references than his realistic portrayal of urban malaise in many works ("A Wild Sheep Chase", "Dance Dance Dance", "Hardboiled Wonderland and the End of the World", "Norwegian Wood", perhaps "The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle", maybe "South of the Border, West of the Sun", "Sputnik Sweetheart" and "Kafka On The Shore"). Quite a few of his male protagonists are passionless loners, unaffected by their wives' betrayals (if any). They are alienated from their families. They are individualistic outsiders, disengaged from community and self-sufficient: able to cook, clean and iron their own clothes. They are disconnected from the girls they sleep with, having sex without emotion or guilt. They had no interest in grades at school. They intentionally avoid the Japanese culture of joining a company and clawing their way up the career ladder. They may be unemployed because they find no interest in work, or, to survive, they may "shovel cultural snow", doing the lowly, thoughtless, thankless tasks that need to be done in society. They keep their heads down. Life to them is pointless and meaningless. They are aimless and irresolute. They have no special talents. We never know their true names nor the names of some of the women that disappear "like smoke" on them. They are suffused with the bittersweet smell of loss. In a Philip Marlowe-ish way, there is a sense that even though they may be unaware of it, their emptiness and cynicism, their thick psychological shells, their chain-smoking coffee-glupping and hard drinking, their distractions of music/food/books, are defensive reactions to some dark past, some unnamed pain. The narrator of "Sputnik Sweetheart" says:

But being neither a besotted fan, a studious student of literature nor a contemptuous literary critic, what was of interest to me wasn't Murakami's writing style nor the fresh tactile perkiness of his descriptions nor his characterisation nor his plot layout nor primarily, his observation of modern consumerist societies, nor the metaphors of subterranean spaces, shadows and telephones nor, err, that obsession with beautiful female ears, but the conflicts in the stories and their resolution. If the common problem with the protagonists is that they are emotionless and so less than 100% human, struggling to live in a chaotic unknowable world, then we expect that it is through their encounters with enigmatic vanishing women and their own fantastical experiences that they remember their pasts, rediscover their sense of self and humanness, and figure out how to get connected again, to work their way out of the labyrinth.

Are the fantastical aspects of the characters' experiences real? Or are they tales they tell themselves, parallel worlds, splintered psyches, doppelgängers, that they create, to sort out their present? Are they journeys of self-exploration that take place in states of consciousness? Are they Heinrich Zimmer-Joseph Campbell type mythologies that provide the individuals the roadmaps to navigate the complex modern world? "The best way to think about reality," declares the narrator of "The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle", is "to get as far away from it as possible".

And what comes of all this thinking about reality? The words "reconnect" and "rediscover" imply solutions that are neat, tyingupoflooseends, satisfying. But with Murakami, there are no fully-flowered bildungsroman conclusions. The most the characters learn is how human beings must survive on their own, how they must cope with their hollowness, their distance from others, in this meaningless world as they hurtle, silently, stoically, towards certain death and oblivion. There is no going back. The best they can do is to accept things they cannot understand and leave them that way, keep dancing, keep spinning, in the here-and-now, to survive in this hostile world where there are neither safe havens nor stable relationships. The idea is almost Taoist (that is, the original Taoism, not the animistic one commonly practised in South-East Asia).

Christian novelists should have in their hands a fair better answer to this pomo existentialism and alienation of self that besets the modern society, more satisfying than advocating the flimsy merging of the Jungian conscious and unconscious worlds or forced engagement with a valueless purposeless universe. But if a Christian wrote such a beautifully-worded novel, would it be globally panned by the literary critics for being unspeakably, well, regressive?

As a kid, I read fiction voraciously, hoping to find in stories the meaning to non-fictive life. Now that I have the truth about real life, these stories yield 2 layers of fiction: the first being the fictive narrative itself and the second, the message behind that narrative, the ontology of that fictional world. Hmmm..it'll be interesting to do a prose piece on that. Very Russian-dolls-like.

Some other Murakami short stories may be accessed online:

"The Folklore of Our Times"

"Hunting Knife"

The typeface for the "Kafka On The Shore" hardcover is apparently Electra (hurhurhur).

Is it just me or does the black cat on the paperback cover of "Kafka On The Shore" look like Jiji in Hayao Miyazaki's "Kiki's Delivery Service"?

[Sidenote 1: Yes, I'm very left in the dust behind the Murakami fan-wagon. ;-). Aiyah. Haven't read much fiction since secondary school.]

[Sidenote 2: The Red Dot Traffic Building houses a nice quiet Pacific Coffee Company outlet with cushy red plush armchairs, leather sofas and Vietnamese paper lamps that is highly conducive for long-term Murakami reading.]

On a blasphemously quick read of many of his books within 3 days, the catchy universality of Murakami, it seems, stems less from his Western cultural references than his realistic portrayal of urban malaise in many works ("A Wild Sheep Chase", "Dance Dance Dance", "Hardboiled Wonderland and the End of the World", "Norwegian Wood", perhaps "The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle", maybe "South of the Border, West of the Sun", "Sputnik Sweetheart" and "Kafka On The Shore"). Quite a few of his male protagonists are passionless loners, unaffected by their wives' betrayals (if any). They are alienated from their families. They are individualistic outsiders, disengaged from community and self-sufficient: able to cook, clean and iron their own clothes. They are disconnected from the girls they sleep with, having sex without emotion or guilt. They had no interest in grades at school. They intentionally avoid the Japanese culture of joining a company and clawing their way up the career ladder. They may be unemployed because they find no interest in work, or, to survive, they may "shovel cultural snow", doing the lowly, thoughtless, thankless tasks that need to be done in society. They keep their heads down. Life to them is pointless and meaningless. They are aimless and irresolute. They have no special talents. We never know their true names nor the names of some of the women that disappear "like smoke" on them. They are suffused with the bittersweet smell of loss. In a Philip Marlowe-ish way, there is a sense that even though they may be unaware of it, their emptiness and cynicism, their thick psychological shells, their chain-smoking coffee-glupping and hard drinking, their distractions of music/food/books, are defensive reactions to some dark past, some unnamed pain. The narrator of "Sputnik Sweetheart" says:

(I) draw an invisible boundary between myself and other people. No matter who I was dealing with. I maintained a set distance, carefully monitoring the person's attitude so that they wouldn't get any closer.Into this banal mundanity is frequently introduced the fantastical: hard-boiled Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett, suburban Raymond Carver with a sort of dreamscape that is very different from the humour of Neil Gaiman or the horror of Franz Kafka but somewhat similar to the permeable Shinto worlds of Hayao Miyazaki (and we like Miyazaki). Kazuo Ishigoro calls it a "deadpan, surreal-verging-on-absurdist comic tone, a willingness to bend the edges of reality in stories set in an otherwise mundane setting". There is a pinch of film noir and David Lynch and a grain of Thomas Pynchon. There is a dash of the metaphoricalism of Richard Brautigan and determinism of Kurt Vonnegut - the characters do not control their own lives (express Sophoclean prophecy as in "Kafka On The Shore" or otherwise), passive recipients of what life deals them. Stylistically, "Hardboiled Wonderland" resembles Philip K Dick, of whom I'm fond, Lewis Carroll and fantasy of the David Eddings garden variety. Some of "The Elephant Vanishes" is more Raymond Carver short stories-ish but lacks its minimalism. Bits of "The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle" are quite Giovanni Boccaccio and Ernest Hemingway simultaneously. In "Kafka On The Shore" Murakami suggests the packed knowledge of Jorge Luis Borges, my all-time top ten favourite fiction writer (yes, should lay off the Nick Hornby) and expressly quotes Borges in "Hardboiled Wonderland" (so Murakami can't be half bad?).

But being neither a besotted fan, a studious student of literature nor a contemptuous literary critic, what was of interest to me wasn't Murakami's writing style nor the fresh tactile perkiness of his descriptions nor his characterisation nor his plot layout nor primarily, his observation of modern consumerist societies, nor the metaphors of subterranean spaces, shadows and telephones nor, err, that obsession with beautiful female ears, but the conflicts in the stories and their resolution. If the common problem with the protagonists is that they are emotionless and so less than 100% human, struggling to live in a chaotic unknowable world, then we expect that it is through their encounters with enigmatic vanishing women and their own fantastical experiences that they remember their pasts, rediscover their sense of self and humanness, and figure out how to get connected again, to work their way out of the labyrinth.

Are the fantastical aspects of the characters' experiences real? Or are they tales they tell themselves, parallel worlds, splintered psyches, doppelgängers, that they create, to sort out their present? Are they journeys of self-exploration that take place in states of consciousness? Are they Heinrich Zimmer-Joseph Campbell type mythologies that provide the individuals the roadmaps to navigate the complex modern world? "The best way to think about reality," declares the narrator of "The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle", is "to get as far away from it as possible".

And what comes of all this thinking about reality? The words "reconnect" and "rediscover" imply solutions that are neat, tyingupoflooseends, satisfying. But with Murakami, there are no fully-flowered bildungsroman conclusions. The most the characters learn is how human beings must survive on their own, how they must cope with their hollowness, their distance from others, in this meaningless world as they hurtle, silently, stoically, towards certain death and oblivion. There is no going back. The best they can do is to accept things they cannot understand and leave them that way, keep dancing, keep spinning, in the here-and-now, to survive in this hostile world where there are neither safe havens nor stable relationships. The idea is almost Taoist (that is, the original Taoism, not the animistic one commonly practised in South-East Asia).

Christian novelists should have in their hands a fair better answer to this pomo existentialism and alienation of self that besets the modern society, more satisfying than advocating the flimsy merging of the Jungian conscious and unconscious worlds or forced engagement with a valueless purposeless universe. But if a Christian wrote such a beautifully-worded novel, would it be globally panned by the literary critics for being unspeakably, well, regressive?

As a kid, I read fiction voraciously, hoping to find in stories the meaning to non-fictive life. Now that I have the truth about real life, these stories yield 2 layers of fiction: the first being the fictive narrative itself and the second, the message behind that narrative, the ontology of that fictional world. Hmmm..it'll be interesting to do a prose piece on that. Very Russian-dolls-like.

Some other Murakami short stories may be accessed online:

"The Folklore of Our Times"

"Hunting Knife"

The typeface for the "Kafka On The Shore" hardcover is apparently Electra (hurhurhur).

Is it just me or does the black cat on the paperback cover of "Kafka On The Shore" look like Jiji in Hayao Miyazaki's "Kiki's Delivery Service"?

4 Comments:

Your pictures have a very nice tint.

Yeah, I like some of them too. :-)

Here's another short story for your collection-'Chance Traveler'

You also missed Tony Takitani. Tsk tsk! ;p

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home