Ingmar Bergman's Wild Strawberries

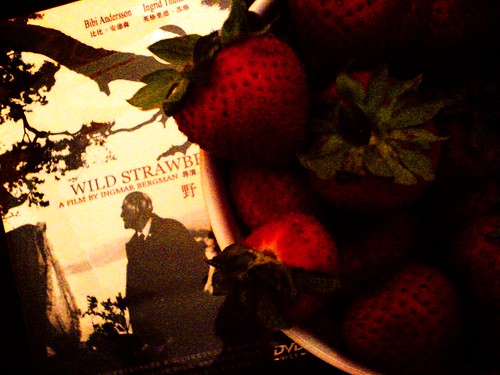

For reasons not always to do with Strawberry Shortcake, males are uncommonly fond of strawberries. So a 1kg haul of macho-yumminess it was, for hand-churned strawberry ice-cream slathered with thick sticky strawberry ice-cream sauce and also for heaping in a great bowl and having very cold and very sweet while lying about watching Ingmar Bergman's Wild Strawberries (Smultronstället, 1957). Eating strawberries in the dark - the petulant Sei Shōnagon would have been disconcerted.

Beyond the vast mound of sweet juiciness, in full monochrome glory, there is the Professor, an old distinguished doctor making a journey to his hometown of Lund to receive an honorary doctorate for his life's work. His 400-mile car journey is parallelled by an interior journey of self-discovery because, you know, it is afterall an arthouse film (go, genre of road movies!).

And what self-respecting self-discovery arrives without a fistful of dreams enroute? So we get an early dream sequence that is all Expressionistic - clocks with no hands, balloony men who fall over and burst and spill dark liquid on the tarmac, and doppelgängers in coffins who (hey, what fun is it lying around all day in a coffin) reach out and grab their shuddering twin. Later dream sequences are Freudian - full of parental-approval-seeking and psychoanalytical childhood scenes that (literally) hold mirrors to the doctor's current state.

The general public adores the Professor. They think he has old-world charm. They think him kind. They think he is the best doctor in the world.

The general public adores the Professor. They think he has old-world charm. They think him kind. They think he is the best doctor in the world.

But, hullo, arthouse movie not Disney animation! So, obviously he ain't all white-toothy and benevolent.

What is the doctor really like? So's we can be sure to get his characterisation spot-on, Bergman names the good Professor "Isak Borg" ("ice fortress" in Swedish). His own daughter-in-law cheerfully describes him as utterly ruthless, selfish and cold as a corpse. And later, his own *ahem* unconscious accuses him of callousness, selfishness and ruthlessness.

Ingrid, the daughter-in-law, notices how this coldness runs in the family: Borg's ancient mom is "cold and forbidding as death" and his son, her husband Evald, "cold and dying".

Pre-filmtime, Ingrid left Evald to stay with Borg because of a dispute over her pregnancy. She wishes to keep the child but Evald is horrified at the thought of bringing a child into the world. He thinks it absurd to do so, having been an "unwanted child in a hellish marriage". He hates his life and wishes to be "dead, stone dead" and not feel anymore pain. Frigidity as a reaction to pain.

His father is no different. Although the good doctor states proudly at the start of the film that his withdrawal from human relations was a conscious decision made when he realised that "in our relations with other people, we mainly discuss and evaluate their character and behaviour", although he thinks he is in control of his own life and that he is an entirely self-made man, we see as the film goes on that just as Evald's horror at child-bearing is founded on his childhood pain, so Borg's coldness stems from the pain of being rejected by his beautiful childhood sweetheart and cuckolded by his wife.

Borg's dreams tell him that however distinguished a doctor he has been, he has been incompetent in living his own life. His first duty as a doctor should have been to ask for forgiveness. It is not the forgiveness of those he has hurt by his coldness that he should seek but the forgiveness of self.

Borg's dreams tell him that however distinguished a doctor he has been, he has been incompetent in living his own life. His first duty as a doctor should have been to ask for forgiveness. It is not the forgiveness of those he has hurt by his coldness that he should seek but the forgiveness of self.

If the movie had been a clarion-call for ice-melting, the fuzzy-wuzzies and touchy-feely-ness, it would have been the cooties. But Bergman isn't quite so binary and reductivist.

What Borg must learn is that his coldness is neither right nor wrong. Therefore, no forgiveness from others is called for. His guilt lies in feeling guilty for who he is. He needs to be able to look into the mirror without flinching, to honestly acknowledge the pain in his past, and forgive himself for feeling guilty for living as he needed to live. He needs to accept the person he is and how he became that person.

So Bergman's main thrust is akin to Borg's answer to the disputing young men (one - a modern man of science who only believes in himself and his own biological death, and the other - a would-be minister) as to whether science or God, rationalism or religion, was right:

Once, someone spoke of how it is a symptom of our sinfulness that we do not truly know ourselves, how we persist in thinking what nice, moral people we are, how we grow so used to our masks and become so skilled at this self-subterfuge that we are quite certain that we are good people; that we couldn't possibly be bad.

Perhaps a further symptom of our sinfulness is how we respond when we do, infact, see ourselves in full decomposing goriness and breath in the full stench of our callousness, ruthlessness, selfishness, greed, lasciviousness and hypocrisy. Do we grasp at that which we have no right to by attempting to forgive ourselves, however illusory the reconciliation? Or do we seek real forgiveness from the one whose laws and design we have actually transgressed and whose person we have offended to our eternal detriment?

Beyond the vast mound of sweet juiciness, in full monochrome glory, there is the Professor, an old distinguished doctor making a journey to his hometown of Lund to receive an honorary doctorate for his life's work. His 400-mile car journey is parallelled by an interior journey of self-discovery because, you know, it is afterall an arthouse film (go, genre of road movies!).

And what self-respecting self-discovery arrives without a fistful of dreams enroute? So we get an early dream sequence that is all Expressionistic - clocks with no hands, balloony men who fall over and burst and spill dark liquid on the tarmac, and doppelgängers in coffins who (hey, what fun is it lying around all day in a coffin) reach out and grab their shuddering twin. Later dream sequences are Freudian - full of parental-approval-seeking and psychoanalytical childhood scenes that (literally) hold mirrors to the doctor's current state.

The general public adores the Professor. They think he has old-world charm. They think him kind. They think he is the best doctor in the world.

The general public adores the Professor. They think he has old-world charm. They think him kind. They think he is the best doctor in the world.But, hullo, arthouse movie not Disney animation! So, obviously he ain't all white-toothy and benevolent.

What is the doctor really like? So's we can be sure to get his characterisation spot-on, Bergman names the good Professor "Isak Borg" ("ice fortress" in Swedish). His own daughter-in-law cheerfully describes him as utterly ruthless, selfish and cold as a corpse. And later, his own *ahem* unconscious accuses him of callousness, selfishness and ruthlessness.

Ingrid, the daughter-in-law, notices how this coldness runs in the family: Borg's ancient mom is "cold and forbidding as death" and his son, her husband Evald, "cold and dying".

Pre-filmtime, Ingrid left Evald to stay with Borg because of a dispute over her pregnancy. She wishes to keep the child but Evald is horrified at the thought of bringing a child into the world. He thinks it absurd to do so, having been an "unwanted child in a hellish marriage". He hates his life and wishes to be "dead, stone dead" and not feel anymore pain. Frigidity as a reaction to pain.

His father is no different. Although the good doctor states proudly at the start of the film that his withdrawal from human relations was a conscious decision made when he realised that "in our relations with other people, we mainly discuss and evaluate their character and behaviour", although he thinks he is in control of his own life and that he is an entirely self-made man, we see as the film goes on that just as Evald's horror at child-bearing is founded on his childhood pain, so Borg's coldness stems from the pain of being rejected by his beautiful childhood sweetheart and cuckolded by his wife.

If the movie had been a clarion-call for ice-melting, the fuzzy-wuzzies and touchy-feely-ness, it would have been the cooties. But Bergman isn't quite so binary and reductivist.

What Borg must learn is that his coldness is neither right nor wrong. Therefore, no forgiveness from others is called for. His guilt lies in feeling guilty for who he is. He needs to be able to look into the mirror without flinching, to honestly acknowledge the pain in his past, and forgive himself for feeling guilty for living as he needed to live. He needs to accept the person he is and how he became that person.

So Bergman's main thrust is akin to Borg's answer to the disputing young men (one - a modern man of science who only believes in himself and his own biological death, and the other - a would-be minister) as to whether science or God, rationalism or religion, was right:

Where is the friend I seek everywhere?(Neither, nor. How very Mary Midgley. But, later!)

Dawn is the time of loneliness and care.

When twilight comes I am still yearning

Though my heart is burning, burning.

I see His trace of glory and power

In an ear of grain and the fragrance of a flower

In every sign and breath of air

His love is there.

Once, someone spoke of how it is a symptom of our sinfulness that we do not truly know ourselves, how we persist in thinking what nice, moral people we are, how we grow so used to our masks and become so skilled at this self-subterfuge that we are quite certain that we are good people; that we couldn't possibly be bad.

Perhaps a further symptom of our sinfulness is how we respond when we do, infact, see ourselves in full decomposing goriness and breath in the full stench of our callousness, ruthlessness, selfishness, greed, lasciviousness and hypocrisy. Do we grasp at that which we have no right to by attempting to forgive ourselves, however illusory the reconciliation? Or do we seek real forgiveness from the one whose laws and design we have actually transgressed and whose person we have offended to our eternal detriment?

Labels: All Given For Food: Strawberries, Films

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home