Leadership, David and the Promises of God

Finance Director I (looking at the garish lights above): Beam me up, Scotty!

Finance Director II (passing round a note with a doodle on it): Eh, guess who? Heeheehee...

Listening to John Woodhouse before and after work was much better.

Listening to John Woodhouse before and after work was much better.Judges

In the Book of Judges, we read about the chaotic anarchic life of Israel as she lurched from one crisis to another, punishment for rebelling against God and worshipping other gods and taking on the abhorrent practices of people who had no knowledge of the true God. They are horrible tales of rape and murder and pillage. But everytime the Israelites found themselves in trouble, they suddenly remembered the God who had saved them in earlier times and cried out to him. Amazingly, God, instead of ignoring them as he could rightfully have done, saved them again and again and again by giving them a judge (not the pasty-faced fogey with a white wig and a black gown but a military leader who would deliver them from their enemies). Unfortunately, these periods of living under the security of God did not last long. When one judge died, the people would forget God again and the whole cycle of events would repeat itself.

At the end of the period of Judges, the situation is summed up succiently: "In those days there was no king in Israel. Everyone did what was right in his own eyes" (Judges 21:25).

There are 2 observations contained in that verse: (1) in those days before they had a king, they had no permanent leadership structure, no fixed political establishment. There was just God, really. There were 12 tribes and the only thing that held them together was God. When there was a crisis, God would raise for them a leader. That leader led Israel for a while, and then he died and they were again without a leader until the next crisis; and (2) there was social anarchy which led to terrible atrocities.

Are we meant to understand that (1) was the cause of (2)? That, because there was no king, there was chaos and anarchy? The text doesn't actually spell out a causal link; it doesn't say that if only Israel had a king, they would be ok. But this sets the scene for Books of Samuel.

Looking for a Leader

God, the creator of the world, had expressed his purpose for the nation of Israel in his promises to Abraham and Moses: they would have their own land and live under God. They would be God's people and he would be their God. They would be a great nation and a blessing to the whole world. But Israel at the end of the Book of Judges was looking distinctly like she was barely holding on to her own land. She wasn't living with God as her god. She didn't look like she could ever become a great nation. She was not much of a blessing to anyone much less a blessing to the whole world.

The issue raised at end of Judges is what kind of leadership do these people need to become the people God wants them to be? Even under Moses, Israel was failure - the Israelites didn't trust God and refused to go into the land he had promised them. Under the leadership of Joshua things were fairly ok but only for a generation. What kind of leadership would make them a great nation through whom the whole world would be blessed?

Leaders in 1 and 2 Samuel

In the Books of 1 and 2 Samuel, we are introduced to 4 leaders: Eli, Samuel, Saul and David.

Eli was a priest and also a judge in the style of the judges in the Book of Judges. He did not care much for the name of God and his sons were worse. So the next leader was Samuel - a prophet and also a judge. He was a godly man whose leadership takes up the first 7 chapters of 1 Samuel. However when Samuel grew old, his sons did not walk in his ways and, as instructed by God, he appointed Saul, Israel's first king.

Saul was a disaster and he was not succeeded by his son, which is the sort of thing you would expect to happen in a monarchy. (One of the benefits of a monarchy is that there is great certainty about the identity of the next leader (barring terrible horseriding accidents and assassination attempts by ambitious relatives). You watch him grow up from an infant to a teenaged prince who will one day take over the throne from his dad. Kingship is hereditary (unless, of course, you are poor old Prince Charles).)

The brand new king who succeeded Saul was not his own son but the son of Jesse (like, who's Jesse?). David was a very different kind of king from Saul. He waited in the wings for much of 1 Samuel and really only took the crown in 2 Samuel.

From Eli to Samuel to Saul through to David, we see the transition from judges to kings in Israel's leadership. So what? Who cares about pieces of the political history of this tiny little nation in the Middle East? It matters because Israel was God's chosen nation; by his grace, they and the office of king were a critical in the preparation of the coming of Jesus on whom the fate of the entire world would rest. As the leadership question took shape in Israel as they moved from Eli to David, we see what kind of leadership the people of God really needed to fulfil their role in God's salvation plan and why, ultimately, Jesus is the leader that the world needs.

David

But first, David or "Great King David" as he was fondly remembered through the subsequent generations, for the years of his glorious reign were not forgotten by the people. David was anointed king while Saul was still on the throne. So things did not go well for David and Saul had designs on his life and spared no effort in trying to kill him. Since David had already been announced as the newly appointed king-in-waiting and God had already proclaimed in no uncertain terms that Saul had been rejected as king over Israel, all that was left was for David to take over the throne. However when opportunities arose for David to dispatch Saul quickly with a sharp implement, he declined to do so.

Even if not for patently godly reasons, self-preservation should have dictated that David should strike Saul first in pre-emptive self-defence. He couldn't be on the run forever with his small motley crew and it would have been only a matter of time before Saul caught up with him.

However, David proved that he was a man after God's own heart by steadfastly refusing to assassinate God's anointed (1 Samuel 26:9,11), even if his own life was in danger. He was more fearful of God's displeasure (26:9) and he trusted fully in God's own judgement and God's own timing (26:10).

David's Suffering

Because of how intent David was on acting rightly in God's eyes, he suffered terribly. Many of the psalms about the suffering of God's king and his ultimate vindication by God, were written in this period when he was on the run and his life was under threat (1 Samuel 18-31). David's righteous suffering was a foreshadowing of Jesus' own suffering, which is why Jesus taught that the Christ "must suffer".

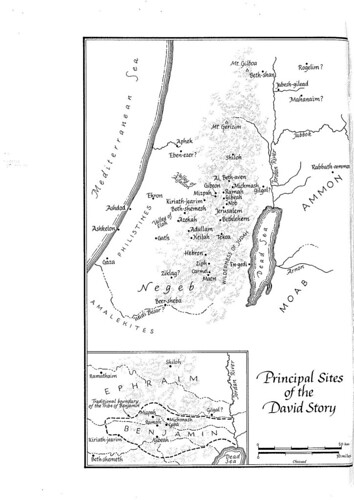

After Saul hari-kiri-ed himself, David's first act as king was to take the city of Jerusalem. His second act was to bring the Ark of the Covenant from where it had been neglected by Saul (the last we heard of it was in 1 Samuel 7) to his new city, Jerusalem. The Ark was the most powerful symbol of God's claim on Israel as God's people. God's presence with his people was represented by his Ark. When the Ark came to Jerusalem, it said that this was the city in which God's king reigned and the real king in the city was not David but God. Which is why David was so excited he danced naked when the Ark was finally brought into Jerusalem.

By 2 Samuel 7, David was enjoying good days. He'd built a palace for himself but he realised that the Ark had been kept in a tent as it had been for centuries. "That can't be right," said David and he wanted to build a nice shelter for it. But God said, through Nathan,"not yet" and "not you". Rather, this is what will happen:

When your days are fulfilled and you lie down with your fathers, I will raise up your offspring after you, who shall come from your body, and I will establish his kingdom. He shall build a house for my name, and I will establish the throne of his kingdom forever. I will be to him a father, and he shall be to me a son. When he commits iniquity, I will discipline him with the rod of men, with the stripes of the sons of men, but my steadfast love will not depart from him, as I took it from Saul, whom I put away from before you. And your house and your kingdom shall be made sure forever before me. Your throne shall be established forever. (2 Samuel 7:12-16)The extraordinary thing about God's promise to David here is that it's unconditional! It's very different from the promise to Saul in 1 Samuel 12 which was conditional (if you are obedient, all will go well. If not, be afraid, very afraid). Of course, even with the current promise, disobedience will be dealt with. But disobedience will not stop David's kingdom from succeeding.

David was not the hero of that story, not according to him. We always like to find something for ourselves in the Bible. We like find the human characters to follow. But David said, "Who am I, O Lord GOD, and what is my house, that you have brought me thus far?" (2 Samuel 7:18). God's promises to David were not to the result of the multitude of David's pious virtues (in fact, after the Bathsheba incident later in 2 Samuel, it is obvious that God's promises to David were in spite of his lack of virtue). God's promises to David had solely to do with God's will, God's grace and God's heart. God set his heart on David. David was God's choice. And it was God's decision to establish David's kingdom forever whatever David might do.

And there is nothing more certain in the world than a promise from God, for whatever God says, he will accomplish in his time. And God's promise to David was this: David will have a son and David's son will be God's own son and the kingdom of David's son will last forever and David's son will build God's house.

In due course, everything God promised in 2 Samuel 7 happened in 2 Samuel 8-10: David did secure his kingdom. David was powerful and just and kind and gentle and generous. We see the goodness of this king and the effectiveness of his godly reign. What an impressive king David was. How wonderful it was to live under he who exercised God's rule in his world.

Many of the prophets from Isaiah to Malachi (eg. Isaiah 11) foretold that the kingdom of David would be revived and, recalling God's promise to David, that a son of David would reign gloriously on the throne forever. The reign of David was important, it was the start of something very very big and very very eternal indeed.

David's Sons

David had a son with Bathsheba named Solomon, and Solomon's kingship turned out to be magnificent and he built a great temple for God (1 Kings 6). What glorious days they were. He was a great and wise ruler who reigned over a secure, prosperous kingdom. The thing that God had promised happened.

But then, it all crumbled. The reality was that the kings in David's line (beginning with David himself) were all flawed. And flawed people can only beget flawed children like themselves. And so we see that the promises of God were only fulfilled in some measure, for a limited period.

By the time we are introduced to more of David's sons, Amnon who raped his own halfsister and Absalom who murdered his stepbrother and conspired against his father (2 Samuel 13-18), we are wondering how God's promises will be fulfilled. What hope is there for God's kingdom? What hope is there for humanity? We see what a fragile unstable weak thing David's kingdom was. His throne was weak, his family was a mess.

This sorry state of affairs was finally put out of its misery in 580BC when Jerusalem was burnt to the ground, the temple was destroyed and the king was made an exile in a foreign land.

It was all over.

Finally! Fulfilment

Or was it? Not for anyone who heard and believed the promises of God, for God's promises can never fail. A few centuries later, in the New Testamental times, the faithful few, having remembered God's promises were looking forward eagerly to the coming of the promised son of David. And a man came preaching about the kingdom of God and he exercised extraordinary power. They ogled at Jesus and asked,"Could this be the one? Could this be the son of David?". Could this the one that Amnon plainly wasn't and whom Absalom definitely could not have been?

And Jesus asked his own followers,"Who do you think I am?". And Peter replied: you are the Christ, the messiah, the anointed one, the son of the living God. That is to say, you are the son of David who is the son of God. And what did Jesus say in reply? You're absolutely right, Peter. I am the one in the line of David. I am the one through whom God's purposes and God's promises will finally be fulfilled. I am the one whose kingdom will last forever. I am whom all those sons of David failed to be. Indeed, I am the son of God. And you know what I will do, Peter? I'll build my church and hell will not prevail against it.

Years later, Peter wrote a letter to Christians and he said:

As you come to him, a living stone rejected by men but in the sight of God chosen and precious, you yourselves like living stones are being built up as a spiritual house, to be a holy priesthood, to offer spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God through Jesus Christ. (1 Peter 2:4-5)The house of Jesus consists of stones who are people who have come to know him and come into his kingdom. We are the temple he is building. We are receiving a kingdom that cannot be shaken because it is the promise that God has made and God does not regain on his promises. And that promise is coming to its realisation as we are built into this kingdom. What a marvellous thing God is doing and what an extraordinary thing that he has let us be part of it! How much shall we serve him, our king and the king of the world, in gratitude.

Labels: 1 Samuel